Destroyed Soviet Mosaics and Frescoes in Armenia

Earlier, I dedicated several articles to destroyed bas-reliefs and statues in Armenia. These articles still attract strong interest, drive steady traffic to my website, and help bring forgotten masterpieces back into public view. Today’s article focuses on another crucial layer of Soviet monumental art: the destroyed mosaics and frescoes of Armenia.

Soviet mosaics, frescoes, and bas-reliefs are among the most striking visual legacies of the USSR. They transformed grey, industrial environments into open-air galleries. Their widespread presence was not accidental but the result of a deliberate state policy that combined ideological messaging with a practical solution to monotonous blank walls. Here, we must again refer to the 1955 decree “On the Elimination of Excesses in Design and Construction” (Об устранении излишеств в проектировании и строительстве), initiated by Nikita Khrushchev.

Like bus stops and bas-reliefs, mosaics and frescoes became a kind of aesthetic loophole and were not classified as “architectural excess.

One of the largest and finest mosaics was created in 1977 by Karapet Yeghiazaryan, Hrayr Karapetyan, Khachatur Gyulamiryán, Vaghinak Mandakuni, Aleksandr Azatyan. The architects of the building were Grigori Grigoryan and Armen Aghalyan. It decorated the façade of the USSR Institute of Telecommunications Research (ՀՍՍՀ Կապի Գիտահետազոտական ինստիտուտ). In the first half of 2023, the building was demolished and the mosaic dismantled, reportedly with plans to reinstall it after the new building is constructed. At the time of its destruction, the Beeline office was located inside the building. Photo Credits: Damien Hewetson

BIG UPDATE

I’m happy to share some good news and update this article.

As of February 2026, the mosaic is being reinstalled on the newly built skyscraper, on the site of the previously demolished building. I have already visited the location twice to document the restoration work and take new photos.

One of the key reasons for the sheer number of mosaics was a formal state requirement: 2–5% of the construction budget for any public building—factories, schools, institutes, hospitals, and even bus stops—had to be allocated to “artistic and decorative elements.” In Soviet planning, this was officially known as “Artistic-Decorative Finishing” (Художественно-декоративное оформление).

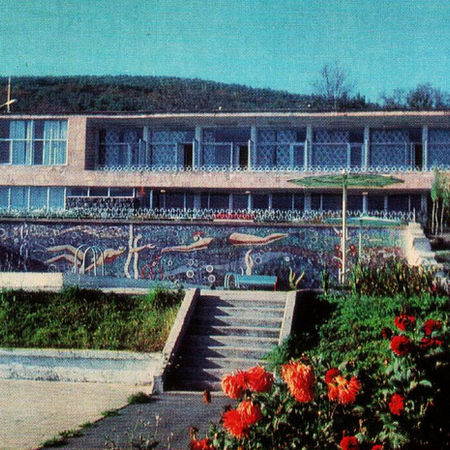

The “Anahit” resort in Stepanavan once featured an impressive mosaic on the wall of its swimming pool. Although the resort still operates today, the mosaic is long gone.

The Art Fund acted as a mandatory intermediary in this process. When a factory or public building was under construction, the building authority transferred the allocated “artistic percentage” to the Art Fund, which then:

assigned an artist to the project;

approved the sketch, ensuring ideological compliance;

supplied materials such as smalt, ceramics, and cement.

In Russian art history, this system is often described by the term “Sintez Iskusstv” (Синтез искусств — Synthesis of Arts): the idea that architecture and fine art should not exist separately, but merge into a single, unified expression of Soviet life.

Before the modern Cascade was built, a mosaic adorned the Old Cascade Waterfall. The artist was the Armenian sculptor and Honored Artist of the Armenian SSR (1967), Derenik Danielyan.

This policy created a vast and guaranteed market for artists. The Union of Artists of the USSR (Союз художников СССР) controlled the distribution of these commissions. For many artists, state orders became their main source of income, resulting in the creation of thousands of works across the Soviet Union, from Moscow to remote Siberian villages.

Unlike murals, mosaics made of smalt (special colored glass) or ceramic tiles do not fade in the sun and can withstand harsh winters. Soviet authorities viewed mosaics as “art for eternity.” Yet even art meant to last forever is gradually disappearing.

About frescoes...

Soviet frescoes, while sharing the same ideological DNA as mosaics, occupied a different niche. If mosaics ruled the exterior, frescoes and other mural techniques dominated interiors. They adorned the foyers of Culture Houses, Culture Palaces, Pioneer Palaces, university lecture halls, and factory meeting halls.

Their tone was academic and historical, focused on Soviet ideology and on the country’s history stretching back centuries, depicting key moments in its past.

In Armenia, many frescoes have survived, perhaps thanks to the fact that they were created by renowned artists such as Minas Avetisyan or Hakob Hakobyan. Others, however—especially works by lesser-known or anonymous artists—have already vanished or are slowly fading away.

The First Class (“Պեռվի կլաս”) restaurant at Gyumri Railway Station once featured a remarkable fresco named "Old Gyumri" by Eduard Edigaryan.

A few low-quality images offer a glimpse of its original appearance. The central section of the mural portrays men dressed in traditional national costumes. In the background, the city of Leninakan is depicted, while the left and right panels of the triptych feature Armenian women turned toward the center. The door is usually kept closed; about a year ago, I asked a staff member to open it to check if the mural might be hidden behind a mirror or panel, but it appears the artwork is lost forever.

From left a guest from Philadelphia, in the center Khachatur Vardparonyan, on the right Hakob Hakobyan. Image credits: Khachatur Vardparonyan (Խաչատուր Վարդպարոնյան), Facebook page.

One of the finest frescoes that has not survived was painted by Khachatur Vardaparonyan and titled Rebirth («Վերածնունդ», 1979). It was located in Leninakan (present-day Gyumri) at the Sock Factory (գուլպա-նասկեղենի ֆաբրիկա), now the Millennium Restaurant. The fresco was not preserved and was destroyed in the early 2000s during renovations.

The fresco discovered in Artik’s former Youth Palace in 2018 during reconstruction works. Photo credits: SHANTNEWS

Initially, the fresco was thought to be the work of Khachatur Vardparonyan, but this attribution was later rejected by his grandson. It was eventually established that the author of the rediscovered fresco was Misha Sargsyan. The work was identified by his wife, Azatuhi Tadevosyan, for whom the discovery came as a complete surprise. According to her, the fresco had been painted more than 45 years earlier and had long faded from her husband’s memory.

When I visited the site in 2024, I was shocked to see that the mural was gone and the building had been turned into a store selling toilets, sinks, and other plumbing fixtures.

“The painting was created in 1967–1968. At that time, we had just gotten married. I suggested that he leave his signature beneath the work, but back then artists were not allowed to sign their paintings,” Azatuhi Tadevosyan told the SHANTNEWS correspondent.

The Culture Palace in Vayk also featured a notable fresco, which was destroyed a few years ago. When I visited the site in 2022, the fresco was already gone, but fortunately, a local worker had a photo of it and kindly shared it with me.

Լուսանկարներ